What do Brian Krzanich, CEO of Cerence AI (formerly CEO of Intel), and Nikesh Arora, CEO of Palo Alto Networks, have in common? They’re both tech leaders who don’t read books. They aren’t alone.

There is a widely-held belief that modern technology has lifted us beyond traditional reading and writing, including — and maybe especially — in workplaces … which makes the cartoon I licensed both funny and painfully true. Why labor over sentences if AI can manufacture them? Or summarize them?

Don’t get me wrong. I believe AI holds incredible promise.

(And another clarification: AI stands for artificial intelligence, which I shouldn’t have to define in 2025 except just seven months ago our U.S. Secretary of Education actually confused — and I truly wish this was satire — AI with A1, as in the brand of steak sauce, when she encountered the acronym in various curriculum planning documents.)

Setting aside AI’s promise, since November of 2022, when ChatGPT was first made publicly available, I’ve devoted many of my waking hours to trying to understand where AI can provably help us, and where it might do harm.

I’ve already blogged here about AI’s societal and safety concerns. This post is about a more intimate and immediate danger. It’s about potential harm to the magical tissue encased in all of our skulls. Brains aren’t literal muscles, but they are just as susceptible to atrophy.

Use it or lose it.

My questions about AI’s utility led me to a timely book, More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI, by John Warner. The author comes to this topic honestly. He has more than 20 years of experience writing for pay, as well as teaching that craft to college students. He also has extensive business experience. He understands the world of agencies — writing for clients. Warner incidentally does not mourn the death of the college essay, felled by ubiquitous AI chatbots. He had never believed it was a reliable way to evaluate writing competence.

What Warner does believe is that only humans can write and read. What’s more, the benefits of writing go beyond mere communication. “Writing is thinking” is both a chief thesis of his book, and a chapter title.

He and many others believe that the intelligence we confer to the text coming out of chatbots is an illusion. Yes, an illusion. Like a magic show. At a Penn and Teller performance, the magic doesn’t occur onstage. The illusion takes place in our minds, as the duo crafts situations where our assumptions and biases fill in perceptual blind spots, and we consequently “see” the impossible. In the same way, conferring intelligence to the writing of robots is a form of anthropomorphism. It looks like a human wrote it, so it must be writing.

We see the labor of an LLM, a mere context engine, as the miracle of human thought. It’s not. It’s a miracle of clustering tokens using staggering feats of math. Remember the chestnut Reading, Writing and ‘Rithmatic? It’s all that third one, not actual writing — nor based on actual reading.

This explains why the true promise of AI wordsmithing is not originality. Far from it. Originality is something that’s a key marker of human intelligence. Instead, AIs produce a synthesis of similar tokenized documents. It’s the rapid sense-making of related project management texts or spreadsheets or sequences of DNA ribbons. Which is amazing, but not thinking. And to quote Warner again, writing is thinking.

Those computations happen much faster and at a far lower cost than entry-level employees, which explains where we find ourselves today, in the worst employment season for recent college grads since the pandemic. AI is a productivity game-changer, but we must acknowledge its limitations. This is something many in technology aren’t doing today. They need to start.

A generation ago, techies already misunderstood reading and writing

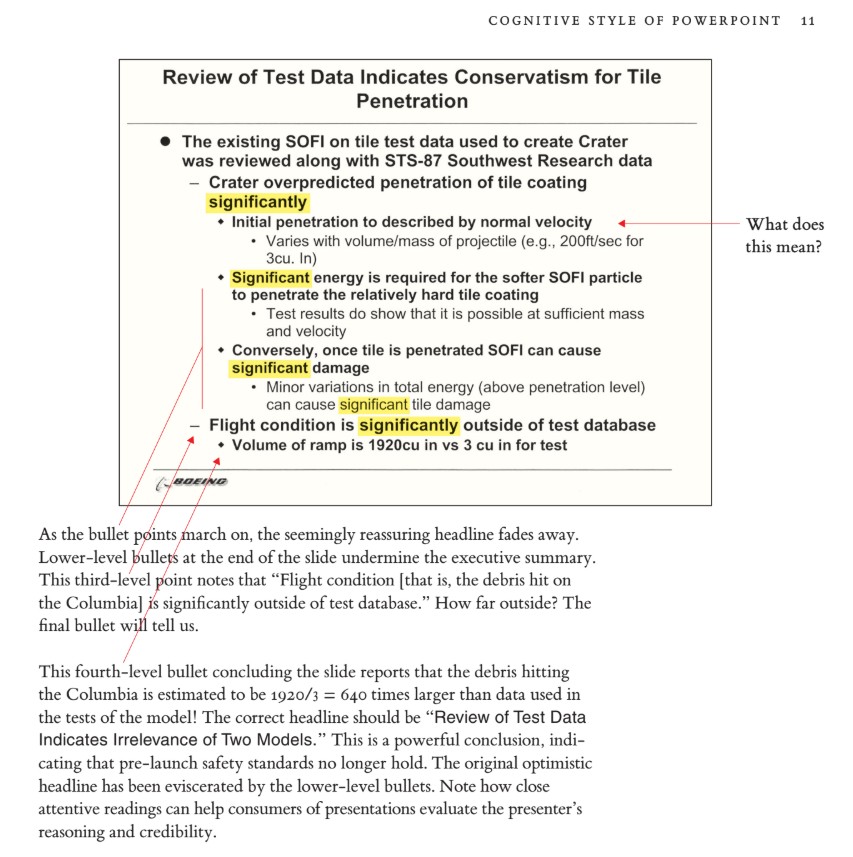

Two decades before Warner bemoaned the degradation of original thought and analysis due to delegating writing and summarizations to bots, something we’re now calling brain rot, there was the Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report. That report criticized that era’s technology du jour: PowerPoint. The board’s report determined that a root cause of the NASA disaster was the “endemic use of PowerPoint briefing slides instead of technical papers.”

Seven lives were lost in the Columbia space shuttle disaster. If better human understanding had been applied at the time, they might still be alive, celebrating this Thanksgiving Day weekend with their families. Scholar Edward Tufte recounted the mistakes in his paper of that time, The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint. Tufte used the report’s findings as further evidence of how nuances of thought are lost when you compress a topic into the bullets dictated by slides.

Tufte’s withering assessment of PowerPoint compared the medium to Madison Avenue pitches, or “infomercials” (a new phenomenon back then). His greatest alarm might have been that schools were eagerly adopting the medium in their lesson plans. The italics are his:

“The core ideas of teaching — explanation, reasoning, finding things out, questioning, content, evidence, credible authority not patronizing authoritarianism — are contrary to the cognitive style of PowerPoint. And the ethical values of teachers differ from those engaged in marketing …

“[Yet] instead of writing a report using sentences, children learn how to decorate client pitches and infomercials … Student PowerPoint exercises (as seen in teachers’ guides, and in student work posted on the internet) typically show 5 to 20 words and a piece of clip art on each slide in a presentation consisting of 3 to 6 slides — a total of perhaps 80 words (20 seconds of silent reading) for a week of work. Rather than being trained as mini-bureaucrats in the pitch culture, students would be better off if schools closed down on PowerPoint days and everyone went to The Exploratorium. Or wrote an illustrated essay explaining something.”

He did concede the practice was “better than encouraging the children to smoke.” So that’s something.

I see a clear throughline from that start of this new millennium to today: The tech leaders. I say this sadly, because I’m one of them. Consider this, also from Warner’s book:

“Writer and critic Maris Kreizman calls [this current moment in AI] the ‘bulletpointification’ of books and believes it is endemic to a tech culture that fetishizes optimization.

Reading and writing are being disrupted by people who do not seem to understand what it means to read and write.

John Warner

“‘It seems to me that there is a fundamental discrepancy between the way readers interact with books and the way the hack-your-brain tech community does. A wide swath of the ruling class sees books as data-intake vehicles for optimizing knowledge rather than, you know, things to intellectually engage with.’”

Warner continues, “Reading and writing are being disrupted by people who do not seem to understand what it means to read and write.”

What is lost in AI-powered bulletification?

Could the point I wished to convey in this 26-paragraph blog post be as compelling if it was filtered through AI and summarized? (And of course I didn’t count the paragraphs to arrive at 26. I had an LLM do that!) … Summarized, perhaps, down to just six? Would this string of stories, references and metaphors be as persuasive to you if they were condensed to an abstract followed by various clusters of bullets and take-aways? I don’t think so. And that thought of mine came from the very act of writing this for you to read. But I’ll leave the final thought on the topic to one of the many technologists who eschew books, possibly even more than those tech CEOs mentioned above. It’s a 2022 quote from convicted crypto swindler Sam Bankman-Fried, recounted by Jonny Diamond in Literary Hub.

I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that. I think, if you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.