This post was originally appeared on the Accenture Careers blog.

TL;DR Choose a time management system that’s built to last, integrate work / life balance into your system and prioritize tasks strategically. Ultimately, keep the promises you make to yourself and your community.

What qualifies me, you might ask, to tell you about time management? After all, the topic has been covered ad nauseum, becoming a defacto publishing category. Well, my two bona fides:

- I’ve researched and studied probably a dozen systems over the years of my lengthy career and found tips you can follow to extract the most out of whatever system you’d care to try

- It’s working! I’m as surprised as anyone that the nuggets of wisdom I’ve gleaned have made me pretty darned effective in my work and personal life

Let’s start with a cliché: The secret to career success is working smarter, not harder. Don’t we all have a trusted family member or friend who told us this? I know I had one, and I was deeply skeptical. Wasn’t this country founded on grit and long hours? For a recent example, the musical “Hamilton” talks about how that Founding Father worked “non-stop” — “All I have is my honor, a tolerance for pain / A couple of college credits and my top notch brain.” Actually, Alexander Hamilton may be the poster child for what can happen to you if you aren’t circumspect about time. He did not work smarter!

Hamilton died in relative obscurity, which is exactly the opposite of what he wanted.

He was known for working tirelessly. One example is his contributions to The Federalist Papers — written with his characteristic eloquence and application of rigorous logic. This contribution alone should have made him a revered historical figure. The Papers became a blueprint for our new country. But Hamilton appears to have thought his cleverness and work ethic were precisely enough to bring him the fame he craved. Nope. He was efficient but not effective and his reputation paid the price.

My mentor was right: You really should work smarter, not harder. We have a limited amount of attention and energy, and more ways to sap both exist today than for any generation before us. We can easily become unmoored, and drift away from what’s truly important. That’s why this is essential:

Regardless of the time management system you settle in with, be sure it starts with a liveable strategy to direct your energies toward the right goals. Only then allow the method to govern how you manage time.

Whither Life Balance?

My studies have been far-reaching, covering both the expected — David Allen’s Getting Things Done and Seven Habits of Highly Effective People — and the obscure: The 90-minute Hour (don’t bother — this could have been written by Alexander Hamilton, it is so fanatical about productivity at all costs), and The Pomodoro Technique (worth considering for the right type of professional). I even tried, circa 2005, an app called Life Balance, a smart approach that never made the jump to iOS, and died with the Palm OS.

My research even includes the mid-century wisdom of — Go figure — our 34th president, Dwight Eisenhower.

I’ve earnestly tried them all, for a while tethering myself to alphabetized folders, both physical and virtual. I’ve tried working in the mini-sprints of Pomodoro — resting every 25 minutes for five, before starting another. I’ve tried the more agile-like week long sprints prescribed by Covey, categorizing everything by the roles I play in life (employee, professional, brother, friend, servant, etc.).

After my travels through these far-flung lands, I’m back to tell you what’s really important in the system you choose, and how you can immediately become more productive and less stressed-out. Here are my five highly subjective tips, borne of trial and error:

- Start with your values. I have to say Covey’s Seven Habits describes this step best. Read how he describes finding your “true north,” and commit to it. And by commit, I mean give it a year or two and see how things go. And if you really like where it’s taking you, also read Covey’s First Things First. That book goes deeper into values, and it finally got me to write a personal Mission Statement. What I wound up with is something that is as resonant for me today as it was when I first wrote it.

- Pick a system. Don’t leave time management to chance. Don’t wing it. It’s no coincidence Covey called them “habits.” He prescribes actions effective people must take that shouldn’t require conscious thought; They should become second nature. And many aren’t intuitive. So get a system and make it yours.

- Keep to-do lists. Recently a co-worker confessed he was getting overwhelmed. We talked about it, and I asked him how he managed his tasks. He wordlessly brought me to his computer monitor. It was papered with Post-Its, resembling the windshield of a car left under a tree on a wet autumn day. Imagine: He would start each day with more than a dozen yellow reminders screaming at him! Always in his line of vision, the tasks reduced his ability to complete them, and clouded his vision of which ones he could or should delegate! They became his master.

- Hide your list. My colleague’s story reminded me how valuable it is that when I capture a new to-do item, I immediately hide it from view. I’m rarely overwhelmed, even when I have a rolling list of 20 or more items per day — most non-urgent ones carried forward to be tackled tomorrow. Although you can rely on paper lists and hide them out of sight, I strongly recommend automated systems: While allowing you to turn away from them, automation keeps them ready for review at any time, wherever you are. That list is the first thing I look at each morning. My online system, Remember the Milk, is installed on all my electronic devices — two computers (one for work, one for personal stuff), my Android work phone and my Apple iPod touch music and podcast player. My tasks follow me everywhere but never overtake me. I am their master, not the other way around!

- Prioritize and refine your lists. For this last tip I need to talk about good ole’ late President Eisenhower. He came up with an enduring approach to prioritizing tasks. It is wisdom that Covey also explores in his books, but here’s a summary:

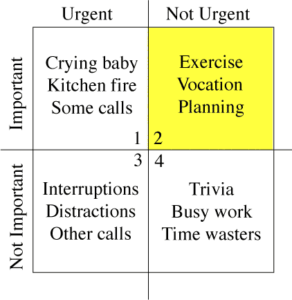

Draw an X/Y graph, with the vertical axis being level of importance, and the horizontal being urgency. Then rank each of your tasks into one of the quadrants. Here’s how that looks:

From there, how to proceed becomes clear:

- Important / Urgent tasks are done immediately and personally.

- Important / Not Urgent get deadlines (which can be ultimately moved) and are done personally. This quadrant is in yellow because it’s the area most of us fall down on, and it’s the most important to our success. We need to spend the most time in this quadrant.

- Unimportant / Urgent task are politely delegated.

- Unimportant / Not Urgent tasks are tactfully dropped.

When you divvy up your work this way, you discover many tasks disappear, which is liberating, and others are delegated — byproducts of which are collaboration and interdependence, qualities that help deepen work and personal relationships (Bonus!).

Drop, Delegate, Do Now or Do Later

Some tasks disappear because they are neither important nor urgent. Example: Does it really benefit you — or your employer — to attend that annual conference, or is it driven by ego … or FOMO? If in doubt, drop it and save yourself the paperwork and the time away from important tasks. You can always find out from others what you might have missed. Start skipping these things and you’ll soon be surprised at how often you hear there was nothing new covered!

Other tasks get delegated. Example: Next time, verbally ask a coworker to respond for the both of you to that group email asking who is bringing what to the potluck. (Promise to return the favor next time, of course. Don’t take advantage of work relationships!). In my experience group emails are often — but not always — the domain of the urgent but non-important. They can quickly become Reply All time-wasters.

Want to know if I deem something unimportant? When you ask me to weigh in on choosing an option, I smile and cheerfully respond “Surprise me.” By saying those words I’ve given both of us a little time back we can devote to other, important decisions. Oh, and another bonus: I’m often genuinely surprised by your choices!

This leaves only important work on your list — except for tasks such as “Follow up with so-and-so on what you delegated.” So what’s truly important? Don’t believe what you’re told. Refuse to let others impose on you what’s truly important. Instead, consult your values and goals. See Tip #1 above.

You Are Your Word

Time management is important because the best employees, the extraordinary parents, the cherished friends — they all have something in common: They do what they tell us they will do. And with every kept commitment, trust — and social and professional esteem — grows.

Here is how I handle a new request: If it’s important and I can do it, I’ll commit to it, and I’ll set a deadline. Then I’ll add it to my to-do list with a deadline well before it’s actually expected. (If it’s urgent and it’s due by 5 PM, I’ll promise that time but shoot for 3:00 and usually complete it by 4:00).

So what have I done? I’ve promised something to my boss, employee, friend or relative. But the task I wrote down in my to-do list was actually a different promise. It was one to my future self. It was a small withdrawal I made against my self-esteem “bank account.”

Once written down, the task is hidden while I tackle other things. I trust myself to do it. When I’m ready to review what’s up next, I will see that task and if it’s time, it tackle it.

When I’m done two things happen:

- I check it off my list and feel great! I’ve once again behaved honorably with myself. The amount I withdrew from my self-esteem account was returned — plus interest!

- I’ve followed through with the original promise. The person I committed to has an opinion of me as well, and I just helped that opinion grow a little.

To both that person and to myself, I have become someone who can be counted on to keep my commitments. One definition of living in integrity is having the same opinion of yourself as those held by your friends, family and coworkers. Good time management moves you closer to that ideal.

Have I missed any good tips? Let me know!

Creative Commons image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MerrillCoveyMatrix.png